I’ve talked a little bit about new, air-source heat pumps (ASHPs) in older posts (I, II). There are some newer products that can work really well in cold climates, but proper sizing, installation, and operation are critical for getting good performance. One key factor is proper location of outdoor units.

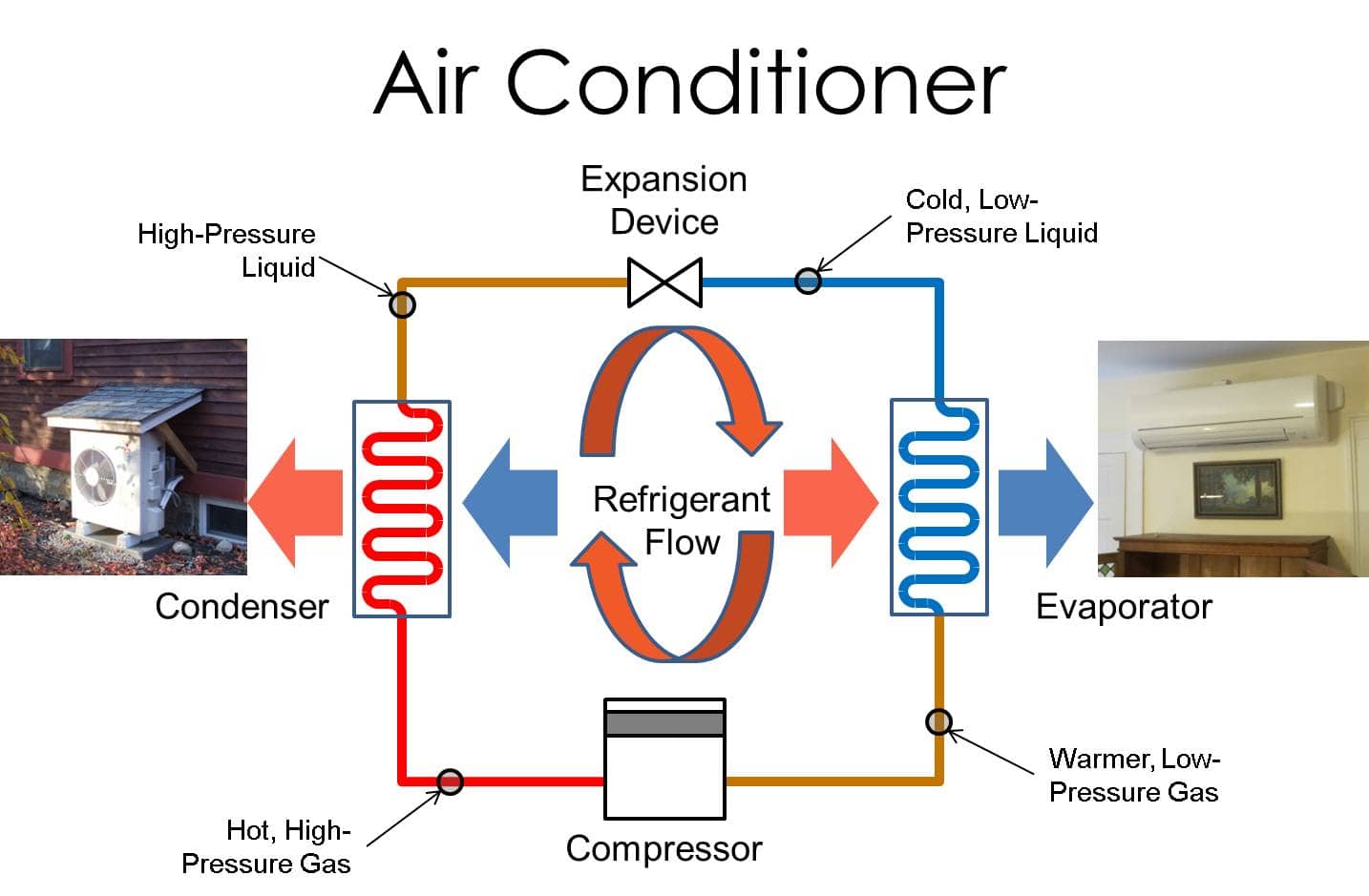

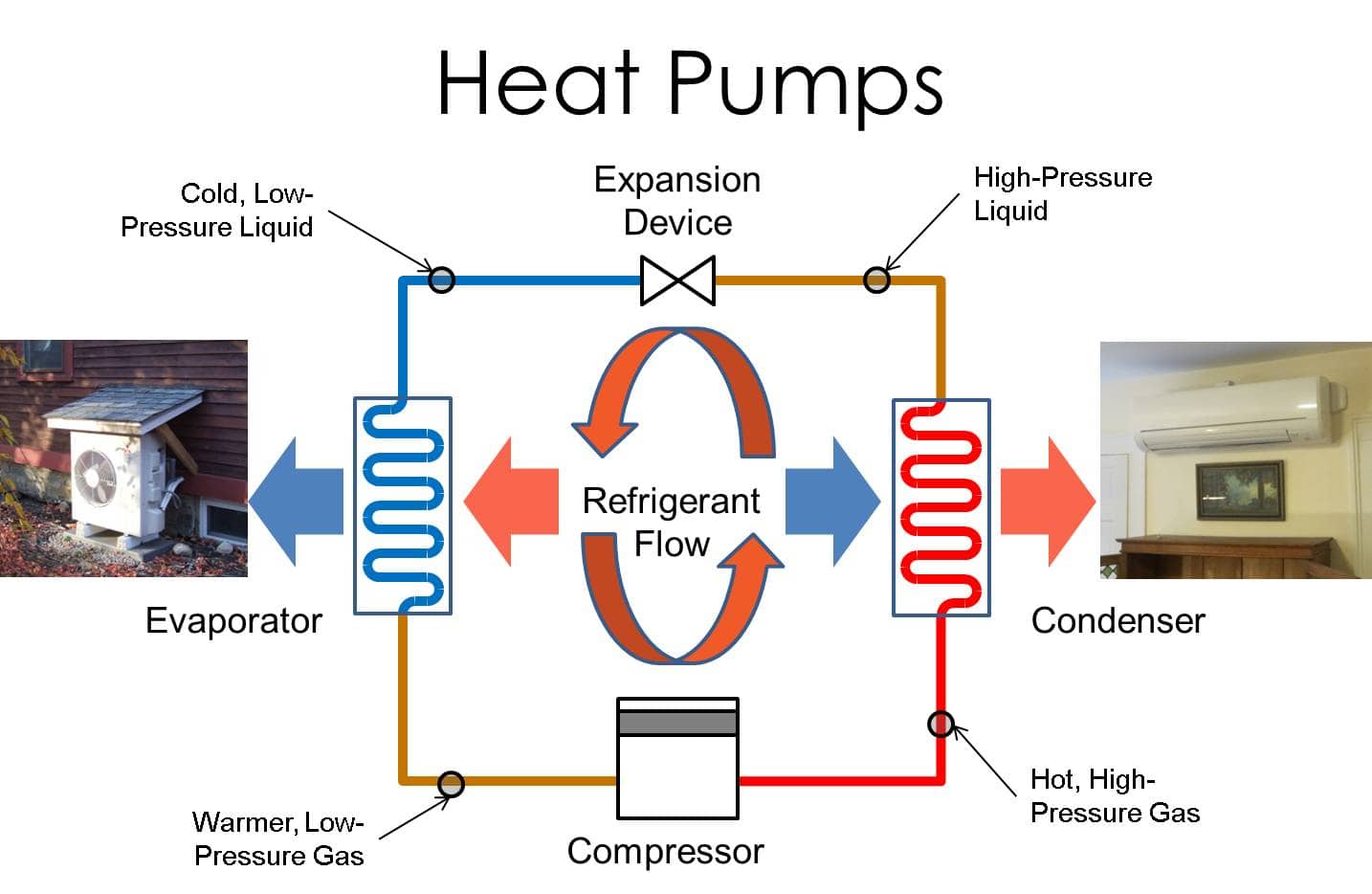

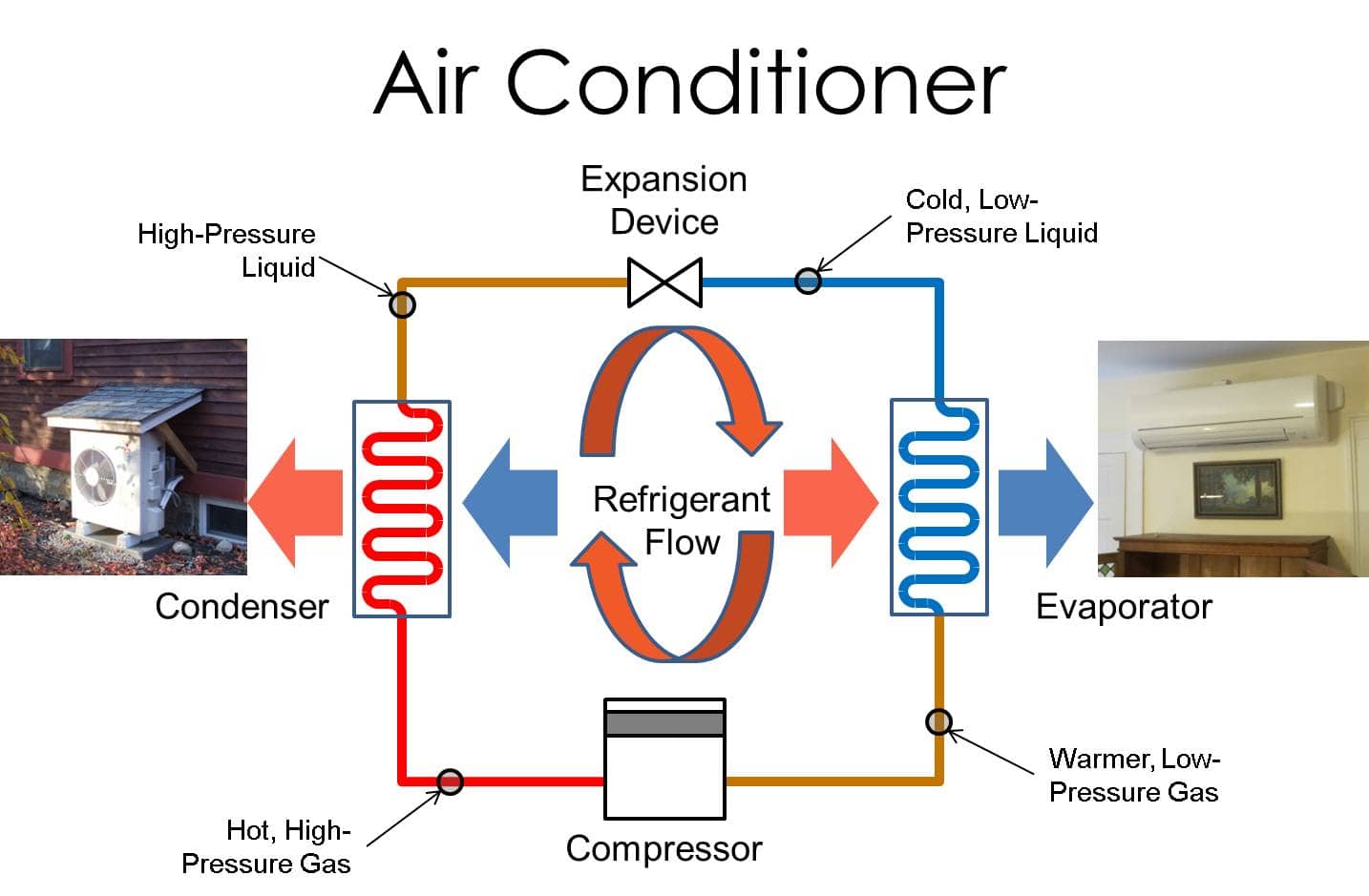

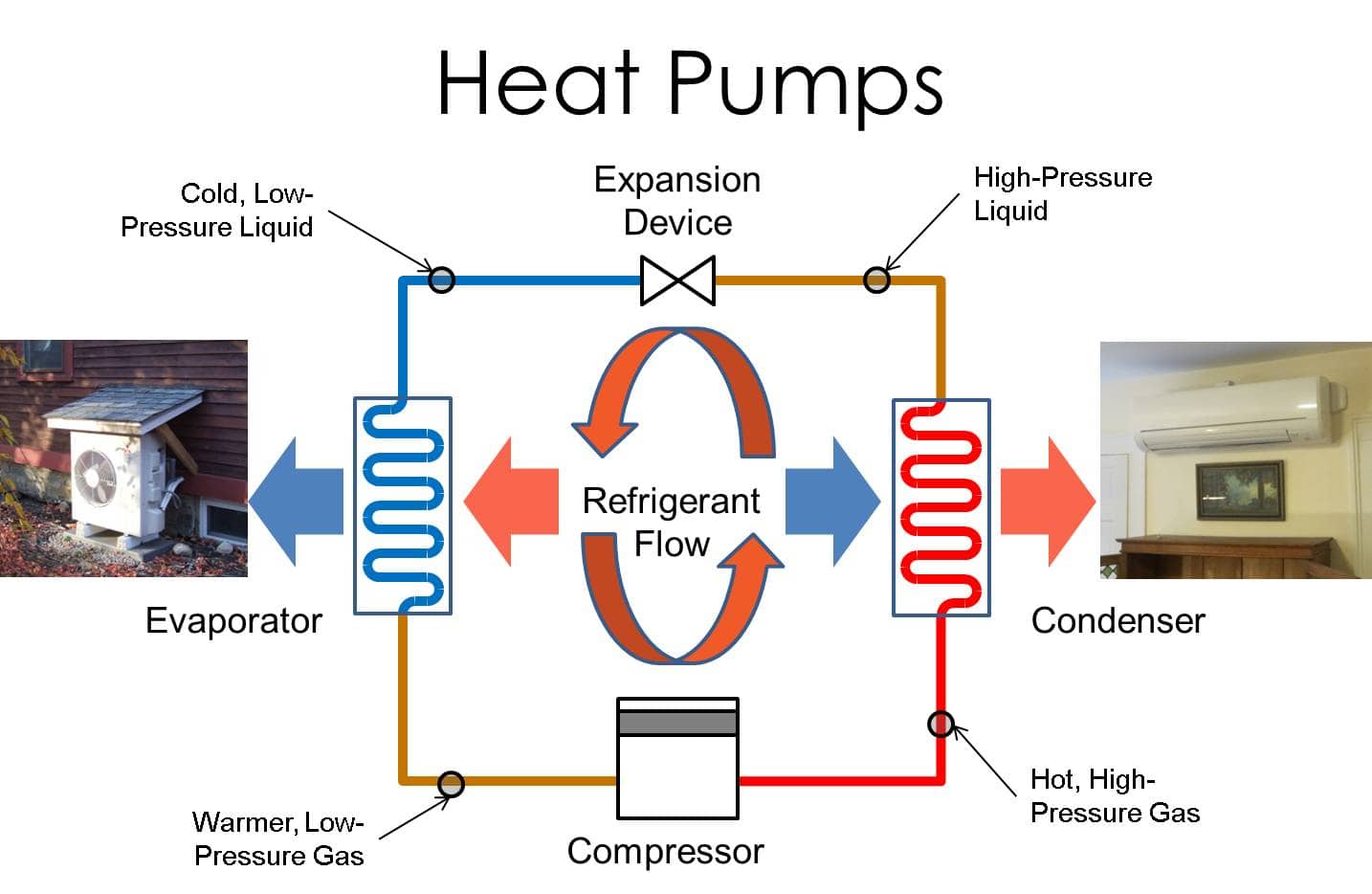

First, a bit of nomenclature. The part of a split air conditioner that goes outside is often called the “condensing unit.” It usually contains most of the key refrigeration components: the compressor, condenser, expansion device, etc. The only key component located inside is the evaporator coil: where the refrigerant evaporates as it removes heat from the indoor air.

In a heat pump, all this is still true during the summer. During heating season, however, the condenser is indoors (releasing heat to the indoor air stream) and the evaporator is outdoors (removing heat from outdoor air). Because of this, calling the outdoor unit a “condensing unit” isn’t quite correct. People still use this term for a heat pump, but I think more people are simply calling it the “outdoor unit.”

During the winter, the outdoor unit removes heat from air blowing through it. Here then, is the key point to remember: If the outdoor unit is encased in snow and ice, it is not able to remove heat from the air. Obvious, yes? But it’s amazing how often there are lapses in this.

This image below is of a new, all-electric home, and this heat pump is the primary heating system. If this was simply an air conditioner, there’d be no problem. But this is located directly beneath the gutter-less drip edge of the roof. A lot of rain and melting snow and ice is going to fall on this heat pump. When this moisture hits the evaporator coil, it will freeze. This is a new home in Maine; I expect problems.

Heat pumps have built-in defrost mechanisms, as some coil freezing is to be expected. However, when heat pumps are subject to extraordinary levels of moisture, the systems defrost A LOT. When doing testing for our study, we ran into this problem in several homes. The heat pump below was beneath a deck; it was protected from direct snow, but as snow on the deck melted, water dripped onto the heat pump where it froze. This heat pump only ran for 10 minutes before it needed to defrost again (run for 10 minutes, defrost for 7 minutes, run for 10 minutes, defrost for 7 minutes…). This is not good. Defrost cycles don’t generally use a tremendous amount of energy, but they usually happen only once every hour or so. If the system is in defrost mode ~41% of the time (7 of 17 minutes), it has at least 41% less capacity.

Drip edges from roofs are pretty obvious, but the snow melt from the deck was a less obvious source of moisture. One other source of moisture that has surprised me is other heat pumps. This is obvious in hindsight, but when heat pumps defrost, there’s liquid water that usually just drips out. What happens if there’s another heat pump below? Or three heat pumps? Before some corrective measures were taken in the installation below, the bottom heat pump really had problems – cumulative ice from the three heat pumps above it defrosting.

But this stacked, wall-mounted configuration was really efficient and convenient for this building; what to do? At this building, the owner installed piping to drain away moisture from defrost cycles (pic below). I was concerned that the ice just might freeze and block these pipes, but that hasn’t happened (and this building has been through one very cold, snowy winter).

I think a more simple solution is a cover. The heat pump below had a simple, site built-cover. It worked fine. Observe also that the unit is on a little pad and some blocks to keep it up out of the snow.

The blocks and pad get it ~12” above the ground. What happens if there is more than 12” of snow? Like maybe five feet? The answer is pretty straightforward: either the heat pump stops working or someone needs to do a lot of shoveling. Here they did a lot of shoveling. You may not be able to tell, but the picture above and below are of the same heat pump. Granted, this was during the record-breaking snowfall in Massachusetts two winters ago (2014-15), but there’s no sense in increasing snow shoveling loads.

So below I think is a great solution. These heat pump outdoor units are NOT located beneath a drip edge or other moisture source, but they still have covers on them for good measure. And they’re 4-5 feet off the ground. This home is in Maine where these heat pump “hats” have become pretty common. Some heat pump distributors have contracted with sheet metal fabricators to make hats for common heat pump models.

I think the installation shown above is great, but this may not be appropriate for all buildings. I’ve heard some stories of heat pumps mounted on wall brackets where vibrations from the heat pumps carry through the building. I’ve not seen this in any projects I’ve worked on – in my experience the outdoor units are very quiet and the vibrations are minimal – but others have certainly reported problems. This might be a bigger concern for older, 2×4 framed buildings. The home above has double 2×4 walls with exterior rigid foam – lots of vibration dampening. If vibrations from wall mounting are a concern, try to use stands to keep the outdoor units well above snow height.