- July 01, 2013

- 0 Comments

- In High-Performance Construction Residential Home Performance

- By Andrea Foss

The Importance of Mechanical Ventilation

During most presentations we give about air sealing and infiltration, like clockwork someone will ask, “but doesn’t the house need to breathe, aren’t we making buildings too tight?” This is a popular green building myth, but people need to breathe, walls don’t. In fact buildings perform best when they’re air tight and we can temper, filter and regulate the amount of fresh air.

We know the symptoms of poor ventilation – odors, humidity issues, condensation on windows, high levels of chemical off-gassing and even elevated carbon monoxide levels. Some of these effects are immediately apparent to occupants (odors, window condensation) while others may be imperceptible (carbon monoxide). Indoor air quality is a comfort, health and safety concern. However, these problems aren’t necessarily symptoms of tight buildings and can occur in all types of construction, old and new, tight and leaky.

We know the symptoms of poor ventilation – odors, humidity issues, condensation on windows, high levels of chemical off-gassing and even elevated carbon monoxide levels. Some of these effects are immediately apparent to occupants (odors, window condensation) while others may be imperceptible (carbon monoxide). Indoor air quality is a comfort, health and safety concern. However, these problems aren’t necessarily symptoms of tight buildings and can occur in all types of construction, old and new, tight and leaky.

Natural Ventilation Doesn’t Work Anymore

In the past buildings were ventilated with outside air naturally when the wind blew and/or it was cold. If this natural ventilation (or what building professionals call air infiltration) ever worked it doesn’t anymore.

“Did you grow up in a barn?” Most of us learned as children the importance of keeping outside air out during heating and cooling seasons. However natural ventilation through building cracks brings unintended moisture and temperature differences that can cause condensation.

Old buildings had no insulation or air sealing, so structural failures caused by condensation within a wall assembly rarely occurred. Building codes now require insulation and air sealing which helps lower our energy bills and keep us comfortable inside. But when infiltration happens in a wall full of insulation, condensation can occur on the cool side of the wall assembly, which over time can rot the framing and cause structural issues. This is why it’s critical to prevent air leaks and better understand the thermal boundary.

Americans spend more time in our homes than ever, almost 15 hours per day by some estimates, and humans give off a lot of moisture. While home we tend to keep the windows closed. We’re also seeing increasing amounts of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) emitted from our paints, furniture and household products that are made with chemical compounds that we know little about. For example, solid-wood furniture does not offgass, but plywood, particle board and foam sure do. How much solid wood furniture do you have in your house? Taken together this means there is more moisture, odors and pollutants added to our homes each day than was the case 30 years ago. The EPA estimates indoor pollutants to be 2 to 5 times higher inside homes than outside.Because of all these indoor pollutants, we clearly need to bring fresh outdoor air into the house.

However, the unintentional natural ventilation air our buildings do get rarely comes directly from outside. In the best-case scenario it creeps in through the various cracks in the exterior walls and windows, but most often comes from the least desirable locations shown in the image below: crawlspaces, garages and attics. Leakage from those locations is certainly not “fresh” air. Do you want to breathe in hot dusty attic air, or damp air from your crawlspace? You just might be.

Natural ventilation is forced through infiltration points which are most often from the unhealthiest locations in homes

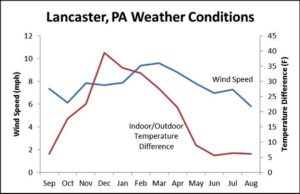

Moreover, unintentional natural ventilation (infiltration) is unreliable and poorly distributed. Infiltration is primarily driven by wind speed and the temperature difference between outdoors and indoors. These weather variables vary day-by-day and season-to-season. For instance, the chart below shows the average conditions for Lancaster, PA. Note the weather fluctuations throughout the year:

- During summer wind speeds are almost 50% lower

- The temperature difference is 6-8 times greater during winter

These erratic conditions cause the building to be over-ventilated half the time and under-ventilated the other half. Also, infiltration is poorly distributed throughout the house. A room with a couple exterior walls and leaky windows will get far more outside air than an interior kitchen or bathroom. Wind and temperature differences drive ‘natural ventilation’ in the form of infiltration in homes. However these factors are highly variable and unreliable.

To summarize the need for mechanical ventilation:

- There are more pollutants in our homes than ever, requiring more ventilation air

- Homes are better insulated and air sealed than they used to be

- Much of the infiltration that does occur comes from undesirable locations

- Even the portion of infiltration that can be considered “fresh air” varies sporadically based on weather conditions

- Having air leaks in an insulated wall, attic or floor assembly can cause condensation and create structural failures.

For all these reasons, relying on air leaks as natural ventilation no longer works. It doesn’t work for normal homes, and it especially doesn’t work for insulated or tight homes.

Build It Tight, Ventilate It Right

The better approach is to provide controlled mechanical ventilation by providing enough air to meet ASHRAE 62.2 and air seal the house to prevent moisture issues, high energy bills, and air from the attic and crawlspace or basement from polluting our indoor air. As the mantra goes, “build it tight, ventilate it right!”

A well-designed ventilation system brings several advantages.

- It allows control over exactly how much fresh air is delivered and when.

- You can adjust the amount of ventilation air if the occupancy changes (e.g. kids go off to college) or shut it down altogether while on vacation, or when windows are open.

- It delivers a consistent amount of air year-round, no matter what the weather conditions.

- It draws air directly from outside, so the air is guaranteed to be fresh.

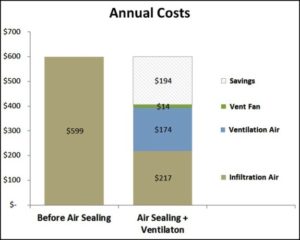

The main disadvantage to mechanical ventilation is the cost to run the fan. There are many different types of systems, with widely varying costs. As the following case studies shows, this additional cost can be more than offset by the savings in reducing the uncontrolled infiltration.

Mechanical Ventilation Case Study

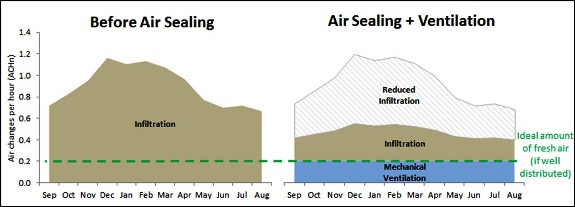

Consider the following single family detached home renovation project in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Before renovation, the house had no mechanical ventilation, and much of the infiltration air came from the attic and basement, providing dirty air to the house. The house was leaky enough to meet ASHRAE 62.2 levels for natural ventilation. But with an infiltration rate of 1.1 air changes per hour, the house was replacing all its indoor air every hour, leading to huge heating bills.

During the renovation air sealing brought the infiltration down by 70% and mechanical ventilation was added to deliver the recommended ventilation rate, which in this case was 0.20 ACHn.

Looking at the annual utility bills, in the original house it cost almost $600 per year to heat the infiltration air. After air sealing this was cut to $217. Heating the ventilation air cost $174, and running the fan cost an additional $14 per year. Not only is the house now less drafty and more comfortable, the indoor air quality is substantially better AND the homeowner is saving $194 per year.

Not every case follows this same savings ratio. If the original house was tighter to begin with there may not have been any theoretical savings. If the mechanical ventilation system were more efficient, there could be more savings.

But remember that mechanical ventilation puts the control in the hands of the occupant, not mother nature. If there seems to be too much ventilation, the occupant can dial it back. If there are indoor air concerns the occupant can increase the rate.

Designing an Effective Mechanical Ventilation System

There are several strategies for designing a good mechanical ventilation system, and there isn’t a one-size fits all approach for homes, multifamily buildings and commercial spaces. It’s important to keep occupants in mind and install the proper controls to make the system work for them. Everyday Green has helped MEPs and HVAC contractors select and size mechanical ventilation systems for all budgets and size buildings, homes and unit spaces. But one thing is clear: relying on air leaks to provide fresh air is no longer an effective strategy. Contact us today with your mechanical ventilation questions.

By Andrea Foss, Director, Mid-Atlantic Sustainability Services